A Conversation with Author and Columnist Carol Weston

By Bascove

New York, NY, USA

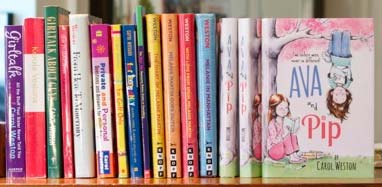

Love 101

Carol Weston has been the "Dear Carol" advice columnist at Girls' Life since the magazine's first issue in 1994. Her first book, Girltalk: All the Stuff Your Sister Never Told You, was translated into a dozen languages, and Newsweek called her the "Teen Dear Abby." She's written for The New York Times, Seventeen, Parents, American Way, Chicago Tribune, Glamour, Redbook, McCall's, and Huffington Post, and been a guest on Today, Oprah, 48 Hours, and The View. She lectures at schools, gives writing courses at colleges and libraries, and has a YouTube channel: Girl Talk With Carol. Among her 14 books are For Girls Only, For Teens Only, Private and Personal, and a "momoir": From Here to Maternity. In 2000, she started writing fiction for kids with her Melanie Martin series, which takes place in Italy, Holland, Spain, and New York. The New York Times said Ava and Pip was "a love letter to language," and she's just finished a nationwide book tour for Ava and Taco Cat, the second book in her new Ava Wren trilogy. I had the pleasure of visiting with Carol at her home in Manhattan for this Conversation.

BASCOVE: Your mother was an editor at House & Garden and your father a television documentarian. What was it like growing up with such culturally astute parents?

CAROL WESTON: I thought of them as Mom and Dad. But yes, they were certainly "word nerds" – in a good way. We played lots of Scrabble, Mom read poetry to us, and Dad made sure we didn't say "like" or "you know" at the dinner table.

Books by Carol Weston (credit: Jen Lu)

BASCOVE: One of your brothers also became a writer. As children were you encouraged to write?

CAROL WESTON: I kept diaries and was more of a writer than reader. In fact, I'm glad my parents didn't encourage me to submit work at a tender age. I'm glad I had the space and privacy to find my voice.

At 19, I announced in the kitchen that I was going to write an essay for Seventeen. Dad said, "You're just going to go upstairs and write an essay?" He wasn't scoffing, but he didn't think it was going to be easy. When Seventeen accepted my story for $100, Dad was so delighted he got teary-eyed. He was born in Odessa, and it was always both sweet and embarrassing that he'd be overcome by emotion at graduations or whenever he was proud of us.

As for my brother Mark, yes, he has written books about Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Japan, and the Electoral College. He writes about the world; I write about the heart.

BASCOVE: Did you always think you would be a writer or were there other paths you might have taken?

CAROL WESTON: In fourth grade, I wanted to be a fourth grade teacher. I remember that we went around the room saying what we wanted to be when we grew up and I told Mrs. Gemunder that I wanted to be a fourth grade teacher. I was being completely sincere but everyone laughed.

BASCOVE: Who are your favorite writers, the ones you can't wait to read when a new book comes out or classics you reread because the writing touches you so deeply?

CAROL WESTON: As a kid, I loved Aesop's Fables. At Yale, I majored in French and Spanish Comparative Literature and loved Rabelais, Racine, Rostand, Stendhal, Balzac, Zola, Molière, all of it! One Hundred Years of Solitude blew me away as did Unamuno. I don't do as much rereading as I would like, and I'm wary because sometimes I'm disappointed when I do. However, I've been a member of the same book club for two-dozen years, and with them, I've read classics such as Tolstoy's Anna Karenina and War and Peace, and Wharton's Age of Innocence and House of Mirth. As for more recent books, I loved Crossing to Safety, The Poisonwood Bible, Life After Life, Buddha in the Attic, The Tender Bar, Unaccustomed Earth, and All the Light We Cannot See, which I was lucky enough to readbefore the reviews, hype, and prizes.

BASCOVE: When did you begin to write professionally?

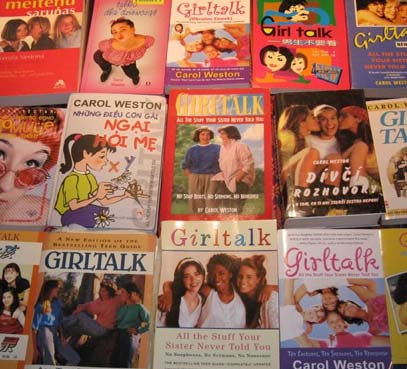

CAROL WESTON: I wrote essays and quizzes for Seventeen, Young Miss, Glamour, Brides, and Cosmopolitan in my early twenties. And I was burning to write a book, but I didn't know what to write about. I had no area of expertise. All I'd done was survive adolescence. Then I met an editor who suggested I write a guide for girls. Girltalk was published when I was 28. Booksellers didn't know where to shelve it because there were no Self-Help or Growing Up sections. It often landed in "Women's Studies."

Carol Weston

BASCOVE: You seem to have a natural talent for talking to girls and young women, often giving them support and advice that they haven't heard or wouldn't accept from any one else. When did you realize that?

CAROL WESTON: My parents subscribed only to The New York Times, so every afternoon I ran to my neighbor Judy's house to read Dear Abby and Ann Landers. I loved their columns. When I married and made friends with my husband's 12-year-old sister, I embraced the "big sister" role. (Of course, now I'm more like a "cool aunt"!)

BASCOVE: Girltalk: All the Stuff Your Sister Never Told You was a great success. Did girls start contacting you personally?

CAROL WESTON: I got very personal letters from girls all over the world, and for years I answered every single letter. I still answer as many as possible. But eventually it weighed on me that I couldn't make everything better just by offering advice, suggestions, help or hotlines. One reason I now write fiction is because that was always the dream, but also because in fiction, I can control the ending. I can make things turn out all right.

BASCOVE: Another acclaimed wordsmith, playwright Rob Ackerman, is your husband. While your writing requirements are vastly different, do you read each other's work while it's in progress? Do you have separate work areas in your home?

CAROL WESTON: We absolutely read each other's work. Over and over. Tabletop. Volleygirls. It's an occupational hazard of being married to a writer. He works at a table in our bedroom and I work in a tiny room off the kitchen and we try to respect each other's boundaries but we interrupt each other a lot too. "Honey, do you know where the charger is?" We'll be married thirty-five years this August! He was 21!

BASCOVE: The Melanie Martin books and your new Ava Wren series are both written as diary entries. It gives them an intimacy that might not arise if the stories were developed with dialogue or third person narrative. Do you still keep a diary?

CAROL WESTON: Yes, but not as regularly. I play catch up on trains or planes. I used to write every evening just to know what I was thinking and feeling. Now after a day of writing, I don't reach for my journal. (I might reach for a book or a glass of wine!)

Foreign translations of Girltalk

BASCOVE: Having written articles and essays for an adult audience, do you ever think you might try writing fiction for adults?

CAROL WESTON: Maybe. Though I have to say, it's remarkably satisfying to write for kids. When kids love your work, they LOVE your work. My office is full of sweet hand-written notes and drawings. And I enjoy the opportunity and privilege of being able to try to turn reluctant readers into avid readers. Sometimes my books really are the ones that turn a non-reader into a reader. And while many kids like fantasy and sci-fi, many want to read realistic fiction, and that's what I want to write.

BASCOVE: You've written 40 letters for The New York Times, correct?

CAROL WESTON: Correct. I'll be having my coffee and suddenly realize that I'm arguing with the paper. I keep my submissions short and pithy – that may be my secret.

BASCOVE: What is coming up next for you?

CAROL WESTON: Ava XOX is coming out in February, and this time I'm tackling not just crushes but, God help me, childhood obesity. In the fall, The Speed of Life is coming out and that's my first novel aimed at 13- and 14-year-olds rather than 10- and 11-year-olds. It's about twelve months in the life of a girl who loses her mother and has to grow up fast. My editor is reading it now and when he gives it back, I'll make final revisions. In March, my own mother died, at age 88, and I'm wondering what it will feel like for me to read my manuscript now. I expect I'll be very sad at certain passages, and I know I'll dedicate the book to her memory.

Links: