A Conversation with Composer Grant Colburn

By Lenny Cavallaro

Methuen, MA, USA

Lesson II in Dminor

I have conducted interviews for well over thirty years, and yet I never cease to be amazed at the "grace under fire" which some of my subjects display. Case in point: Grant Colburn, who was getting ready for his wedding when I approached him on deadline. Ah, well. Such minor distractions can always be put aside!

Colburn is certainly a versatile musician – pianist, harpsichordist, and most notably, composer. In his creative work, he turns to the idioms he enjoys and reveres: the styles of the 16th through 18th centuries.

Colburn contributes to Harpsichord and Fortepiano Magazine, and has also written features for Early Music America Magazine (EMAg). Moreover, until roughly a year ago there was another, somewhat surprising aspect of his musical life: involvement with alternate rock and roll. However, I was anxious to focus on his compositions and Vox Saeculorum, a group of 21st-century composers who write baroque music.

Grant Colburn

STAY THIRSTY: Let me begin by asking you to tell us a little about the founding of Vox Saeculorum and, more recently, of its Facebook forum, which has truly been your own brainchild.

GRANT COLBURN: It was actually Mark Moya who "founded" Vox Saeculorum, although I somehow emerged as a "co-founder" after the fact. It's an amusing story.

I began writing baroque music when I was about 16 with the idea that is still true for me today. Baroque music made me want to be a composer, so what other kind of music would I write but my favorite kind? I finally got onto the Internet in the 90's and started finding out who else in the world might have had my strange interest in writing new baroque music.

STAY THIRSTY: No kidding! I wish I had known. By 1989, I was writing baroque works, and I very much feared I was alone!

GRANT COLBURN: Well, you certainly were not, and I guess I have you beaten by a few years, since my first pieces were from 1982. I remember finding some concertos by Mark Moya (who I think was still in his teens at the time) as well as music by Michael Starke and Giorgio Pacchioni. And this was so early that these were all in midi files! At the time I don't think I ever corresponded with any of them.

Then one day a few years later I came across the Vox site, which already had people like Miguel Robaina and Roman Turovsky as members. I recognized the three names above and asked to join. Obviously, then, I couldn't possibly have been a "founding member"! However, once I had submitted my music and was added to the roster, I thought to promote Vox, much as I had been doing for the original rock bands with which I played. That is how I ended up writing the article for EMAg. At that point Mark said that since I had the time and interest to make our presence known, he wanted me to consider myself a founding member, so I started to scour the world for other like-minded music writers.

Originally the Vox site had no means for the members to communicate with each other or the media page, so at first I thought to simply add some kind of chat room that linked to the website. With the advent of Facebook, I made a Vox page much like a page one might construct for a band. This sufficed to find "likes" and have a place for people to connect, but little more. About a month ago, after joining the Tonal Composers page, I realized that what Vox had was a "fan" page, and that Facebook had subsequently created "groups" where everyone could post things and interact much more easily than on the original page.

STAY THIRSTY: So that's how the Facebook group page was born!

GRANT COLBURN: Exactly! Its primary purpose is for the members to have a place to share and discuss aspects of baroque composition in a positive environment, exchange ideas, help one another, and offer critiques when asked for. Its other purpose is to serve as a place where those who have written only a few period pieces can share them, and those aspiring to learn how to write authentic period music can get help and advice. Hopefully, we'll also draw in early music performers who might take an interest in giving the "world premier" of new period works by living composers.

Allegro from Sonata #I

STAY THIRSTY: Let us hope so. First, however, let me ask the more delicate question – one which has certainly crossed my mind on more than one occasion: What is the future – if there is one at all – for this type of new "old" music – or is it "new" old music? What sort of response has it drawn thus far – and in particular, what sort of resistance have you and your colleagues encountered from the "musical establishment"?

GRANT COLBURN: I'm not sure if there is a future for new "old" music – but then I'm also not sure if there is a future for new "new classical music"! Five or ten years ago I wouldn't have thought it would get as popular as it has. Many of us are also performers, so at least our music gets some exposure when we play it. Moreover, three of our members are directors of their own chamber orchestras: Hendrik Bouman, Anton Martynov, and Federico Maria Sardelli. That makes a huge difference, both in gaining an audience for the music and giving people "evidence" of the quality of new period music written today.

It's one thing for people to hear a solo harpsichord or lute piece. It's another to have a 20-piece ensemble ripping through an intense concerto that sounds every bit as good as something by Vivaldi or his lesser-known contemporaries. The response from audiences as far as I know has always been positive, particularly when the conductor can surprise the audience by having the living composer come take a bow for his ancient-sounding work!

The resistance, when it exists, comes mostly from other non-period composers and those tied to academic institutions.

STAY THIRSTY: Particularly the academics! I can tell you horror stories on that score.

GRANT COLBURN: Well, the modern perspective for classical music is that everything should be "new" and "experimental" all the time, so colleges don't really want to promote music that deviates from the norm, while local chamber ensembles usually want to play it safe and stick to the masters (Bach, Handel, Vivaldi, et al.). Thus, it's rare enough to hear lesser-known actual baroque composers, and even more unusual to have them play something by one of us.

The good news is that I think most classical audiences are tired of having everything sound "new" and unfamiliar all the time.

STAY THIRSTY: Yes – dissonant, harsh, percussive, and generally unpleasant!

GRANT COLBURN: … and we offer them the possibility of letting in some fresh air. The other nice aspect is that early music performers routinely improvise and embellish repeats.

STAY THIRSTY: Indeed. I am constantly reminded of Glen Gould, who insisted on numerous occasions that he was "not a pianist, but … a composer whose instrument happens to be the piano."

GRANT COLBURN: Right! And this idea is not so far removed from what I'd really like to see: performing composers appearing once again with their ensembles, premiering their works and hopefully those of other composers as well.

STAY THIRSTY: You are a harpsichordist by original training, and you obviously developed an affinity for this style of music early in your development as a musician. However, there is a world of difference between performance and composition. How did you gravitate toward composition, and what new challenges did you face?

GRANT COLBURN: Actually, I am a pianist by training. I did the usual Midwestern American piano lessons. My first love – when I was 10 – was ragtime, but that then switched into Bach inventions and other baroque music. I first heard a recording of a harpsichord in music class while in grade school: Cimarosa's Sonata in G, performed by Igor Kipnis. I fell in love with the sound and amazingly enough found out that Kipnis offered summer harpsichord music camps in Indiana. A few years later I sent in an audition tape and was accepted, and my parents (both music teachers) actually drove me there and paid so I could attend the two-week course. I went back the following year.

Surprisingly – call it a past life thing or something – I also got drawn to the English baroque by about the age of 13. My piano teacher had a bad piano edition of the music of John Blow, and from that point English baroque music became my main focus.

STAY THIRSTY: Indeed, you "channel" those composers magnificently!

GRANT COLBURN: Thanks, but back to the composition question: I started writing music about the same time I got serious as a piano player. The first baroque keyboard pieces I still consider good were written when I was around 16 – nothing fancy, but I like them to this day. I make my living now as a piano player and accompanist both for churches and the local university. The reason I got good enough to play piano for a living is that I had an incredible appetite for learning how music was written. I didn't just study pieces to perform them, but instead I read through them to determine how the composer wrote them. From doing that, I have become a really good sight-reader. This has enabled me to accompany students, which I can do with little or no rehearsal on my part.

STAY THIRSTY: I'm green with envy; my sight-reading has always been dreadful!

GRANT COLBURN: Ironically, though, like so many other good sight-readers, I find the skills have actually somewhat hampered my ability to practice and perfect the music. So although I play in front of people all the time, I don't consider myself a great performer.

STAY THIRSTY: This is true of many keyboardists, in particular. Also, many of those who sight-read effortlessly find it difficult to memorize – and many who memorize easily, sight-read poorly. On the other hand, this may actually have given you more motivation to compose.

GRANT COLBURN: Exactly. And yes, I am terrible at memorizing music. I much preferred the idea of composition, where I could "perfect" a piece of music, write it down, and then let someone else play it. I also like the aesthetic "look" of scores, so I have spent a lot of time learning how to make them look aesthetically pleasing. Overall, I'd rather sit in my living room (or in a performance hall) with my score in my hand and listen to someone else play my music than appear as the person on stage.

However, the way this all ties into becoming a period composer is actually rather simple. I am quite passionate about history. When I studied the piano, I did it to learn more about how baroque music was constructed, because it was my favorite classical music. When I got old enough to go to college, I considered majoring in composition but soon found out that that would entail writing loads of "modern" music, in which I had little to no interest. Instead, I got a degree in piano performance in hopes of making a living and continued writing the music I liked as my hobby, albeit a very serious hobby. And through Vox I have learned that others share this hobby, and this has inspired me to take it more seriously.

STAY THIRSTY: Among your own works, which are your favorite compositions?

GRANT COLBURN: Well, I guess my favorite pieces are also the ones I'd consider my best, and "best" is a strange thing to ponder, because I will also write new music that I know from the start won't be my best music.

For example, the collection of music I am currently trying to finish is a book of Six Voluntaries for the Organ or Harpsichord, and there are two things that make it a challenge. First, these usually have very few pieces in binary form, so with a single exception, I have avoided the binary form I so frequently use. However, the bigger challenge I made for myself was deciding that each voluntary would have a fugue.

STAY THIRSTY: A fugue? We don't usually find those in books of voluntaries.

GRANT COLBURN: Actually we do, but usually the first few voluntaries have trumpet (or cornet) or flute pieces, which are basically allegro movements, and then the composer writes two or three voluntaries at the end that contain fugues. Fugues are still a new thing for me, since I've only written only three others before. So I added to the challenge by deciding all the voluntaries would contain fugues, making them similar to the preludes and fugues one finds in Bach, but with a definitely English flavor.

STAY THIRSTY: I've had only two of my fugues published, and the third is still a "work-in-progress".

GRANT COLBURN: Well, here's where it gets interesting when we are talking about what I think is my "best" music. The person who commissioned me to finish the book asked me to write one that would be more substantial than the rest. This voluntary will be Number V, and I have all of it finished except for the fugue. If I can write a fugue that is on the same level as the rest of the movements I already have finished, I think it will be one of my new favorites.

STAY THIRSTY: Good luck!

GRANT COLBURN: However, the point I was getting to was that I have also started Voluntary VI and know it will not be one of my favorites! It's not that it won't be nice, but after working on the multi-movement Number V, I decided the last one should be short and sweet and simple. As you can see, I don't write each piece believing that it will be better than my previous one. Just as period composers did back in their day, I abide by the concept of music as a craft rather than a product of genius. Even in this volume I am finishing, some will reach the heights of my ability, while we can say the others will be "easier." This book also contains my first fugue. I began it when I was 19 while in college, but it had to wait almost 30 years to be completed.

Other favorites pieces include the two harpsichord concertos, especially the second one. They were both challenges to me in branching out from my usual writing by having to use concerto form and also writing for four-piece chamber orchestra.

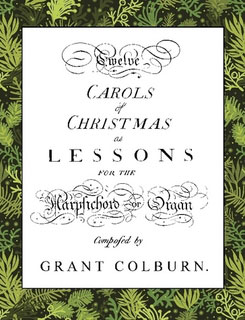

STAY THIRSTY: In addition, we should mention your Twelve Carols of Christmas as Lessons for the Harpsichord or Organ, which is billed as "a book of arrangements in baroque and renaissance styles of well known Christmas carols for solo harpsichord, organ or piano."

GRANT COLBURN: Yes, I am proud of those as well, though technically they are merely arrangements rather than original compositions. Still they have actually been my most successful works in sales and popularity.

STAY THIRSTY: There's a market for new period music if one can find it!

GRANT COLBURN: True! Other favorites are funny to mention, because their abstract names don't really tell the listeners much. Sadly, four of them are in an unfinished volume that contains a favorite work, my Lesson in D minor. That manuscript also includes a two-movement lesson inspired by Scarlatti and Seixas, rather than my usual English sources. And those I really like, because I thought to broaden my horizons and try to write something different.

STAY THIRSTY: Of course, you're not alone in "channeling" Scarlatti!

GRANT COLBURN: Right. At the time fellow Vox member Gianluca Bersanetti was writing a set of sonatas influenced by Scarlatti, so I thought to try to write one, also. I surprised myself and think it – or they, if we count both movements – turned out really well.

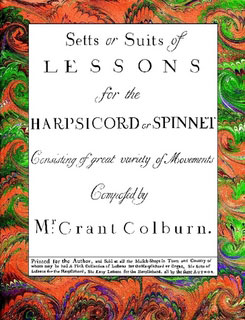

Then there are many of the suites/lessons I wrote for my book, Suits or Setts of Lessons for the Harpsicord. [Colburn intentionally uses "old English" spellings. – ed.] These, too, are among my favorites. Again I made myself a challenge and wrote a book of music influenced by English composers from about 1715. The music is somewhat more serious and uses thicker harmonies than those found in my usual, lighter pieces. There is no better feeling than creating a challenge for oneself and then feeling one has met the challenge!

STAY THIRSTY: Can you tell us anything more about this volume?

GRANT COLBURN: Certainly. It contains three other works I consider among my best. One is the Lesson in D minor, which though fairly simple, is one I enjoy a lot. Fernando de Luca did a nice recording of it. Another lesson in that book is an experimental work in which I incorporated my experience with progressive rock – a whole other topic! – and wrote what I consider completely legitimate baroque pieces that all happen to be in odd time signatures.

Allegro Moderato in 7

STAY THIRSTY: Odd time signatures? Such as –?

GRANT COLBURN: The first piece is an allegro in 7/8, which is followed by an adagio in 5/4 and a rondo in 7/4, and it concludes with a Jigg in 11/8.

STAY THIRSTY: Not exactly the standard fare for baroque!

GRANT COLBURN: Not standard fare for almost any classical music until the 20th century! Then the other favorite from this book is, or more accurately will be a sonata for flute and harpsichord, of which I have two of the three movements written. This, too, was a bigger challenge than my usual work, and is a major reason that the entire book has yet to be published.

I can probably also point to pieces and lessons sprinkled through my other volumes that are still among my favorites. Generally, however, as I said before, sometimes I feel that I am writing and hitting a new "high" for quality and originality, while other times I know that I am not. Nevertheless, each piece deserves to be finished even if it's not always "better" than the last one.

STAY THIRSTY: I think we can also say that music of this sort deserves to be and indeed must be written, even if it sometimes sounds very similar to what some other composers wrote centuries ago. More to the point, people should learn to enjoy it – or not – based solely on how they respond to the music, and not by when it was written.

This brings to mind a few thoughts, including two from your excellent article, "A New Baroque Revival: Breaking through the Final Taboo," in Early Music America. You alluded to Glen Gould's piece, "The Prospects of Recording," which appeared in High Fidelity. Gould noted "the shifting of aesthetic judgment due to factors outside of the points of idiomatic evolution," which – for the purposes of our discussion – is to say that reaction to a newly discovered work by some famous 18th-century composer would invariably be quite different than reaction to the identical music composed in 2015.

You also cited the Canadian musicologist, Bruce Haynes, who explained that the only way a contemporary "period" composer's works "are likely to be accepted at face value is if he identifies them as the work of some musician of the appropriate period." This brings to mind Fritz Kreisler, who obviously felt such pressure, also; that is why so many of his pieces were attributed to composers of the past!

Sonata for Harpsichord and Flute, 2nd movement

However, I'd like to interpolate a story attributed to Olin Downes, the gist of which can be summed up thusly: "Suppose you kissed the wrong woman in the dark and truly enjoyed the kiss. Then, when the lights went on, you recognized your error. Would that mean you had not enjoyed the kiss?" I am sure you can see where I'm going.

GRANT COLBURN: Yes, exactly. Classical music is judged more on how it influenced the succeeding generations rather than on its own terms. The prime example is the music of Bach, who for the average music listener is considered the baroque composer. However, in his own time Bach was considered an old fashioned fuddy-duddy. He basically influenced almost no one of his own generation, but was rediscovered by future generations, who then considered his music to be the culmination of the baroque style. Meanwhile, a composer like Telemann, who truly did represent the culmination of the baroque style, was considered a hack for quite a few years, before people realized his own uniqueness regardless of whether he influenced succeeding generations.

STAY THIRSTY: A number of artists have recorded your works. I think at once of harpsichordists Fernando de Luca and Andreas Zappe, with whose work I am quite familiar. Also, Roman Turovsky transcribed some of your compositions to baroque lute. What is it like for you, as a composer, when you hear someone else's interpretation of your music – particularly when that might be quite different from your own?

GRANT COLBURN: Well, it's interesting, because I try as much as possible to follow the standards of actual baroque music, with limited indications of tempo, few expression marks or dynamics, etc. I want my scores to look exactly like music from the baroque. But just as was true for composers of the period, one can end up with performances that are much different than were originally intended, especially with regard to tempos. So now, when I know someone is planning to record something I wrote, I at least give him/her some idea of tempos and other expressions, so that the interpretation will at least be close to my intentions. There's nothing worse than knowing someone made the effort to record or play something I wrote but not feel I can completely endorse it as representative of my music.

STAY THIRSTY: I agree with you completely. I've had performers play music quite differently than I had conceived it, although most of the time I've been quite gratified with the result – most recently when Fernando de Luca recorded my partita.

Let us hope we can all avoid any disappointments on that score. Meanwhile, let us also await the successful release of Six Voluntaries for the Organ or Harpsichord – and many more works from Grant Colburn.

Links:

Grant Colburn

Grant Colburn IMSLP

Vox Saeculorum

Vox Saeculorum on Facebook

Lenny Cavallaro at Stay Thirsty Publishing

Lenny Cavallaro - Composer and Pianist and at Forton Music

Lenny Cavallaro at Broadbent & Dunn Ltd.