A Conversation with Noir Film Czar Eddie Muller

By Mark Yost,

Chicago, IL, USA

Eddie Muller and Kathleen Maria Milne

Ask almost anyone to name the man most associated with film noir, and Humphrey Bogart would win hands down. A close second should be Eddie Muller. He is the modern-day Dean of Film Noir. He founded the Film Noir Foundation to preserve the shadowy characters and dire plots of the movies of the 1940s and '50s. He started the NOIR CITY film festivals to expose more people to these great films, many of them shot in dark, iconic corners of his native San Francisco.

This summer, he's hosting Friday Night Noir on Turner Classic Movies, introducing viewers to some of his favorite film, some well known and some that have been mostly forgotten (or would have been lost without the Film Noir Foundation).

And later this fall, Muller and Bogart will literally be together at the Humphrey Bogart Film Festival in Key Largo, Florida. Eddie will introduce many of the films featuring Bogie and his wife, Lauren Bacall, a film noir heavyweight in her own right, who died in May.

Muller recently sat down with Stay Thirsty Magazine at his home in San Francisco to talk about the genre, where it came from, where it's going, and why he can't turn away from a good, dark tale.

MARK YOST: What is film noir?

EDDIE MULLER: Well, considering that endless books are still being written about it perhaps no one has a definitive answer. But for our purposes, I'll go the All-American route: it's an organic artist movement that swept through Hollywood in the 1940s. It developed when American hardboiled crime fiction was crossed with a particularly European style of visual storytelling that had its roots in German expressionist cinema. Many of the foremost directors of noir—Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, Robert Siodmak, Otto Preminger—had learned their craft in Berlin at the end of the silent era. When they applied their visual approach to a particularly dark strain of crime story popularized by American writers such as James M. Cain, Dashiell Hammett, and Cornell Woolrich … film noir was born.

That said, we're learning now, through further cultural archeology, that noir wasn't an exclusively American development. Examples from the same era are being discovered not just in Europe, but in Mexico, Japan, Scandinavia, South America. The noir movement was more expansive than its scholars first realized.

Courtesy of the Film Noir Foundation

MARK YOST: Why did you found the Film Noir Foundation and what is its purpose?

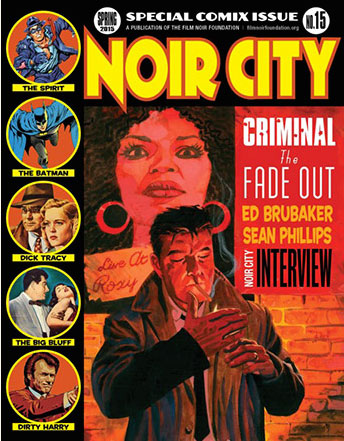

EDDIE MULLER: I founded the Film Noir Foundation [FNF] to gain access to film archives that my NOIR CITY festivals wouldn't have had without the status of a non-profit corporation dedicated to the "educational edification of the public." When we started garnering decent box-office I decided that the right thing to do was reinvest the profits in the rescue and restoration of films that might otherwise be lost. We're probably the only film outfit in the nation that operates on a closed-loop system, using the proceeds from exhibition to actually find, restore, and recirculate "missing" films. Among the movies we've saved from oblivion: The Prowler (1951), Cry Danger (1951), Try and Get Me! (1951), Repeat Performance (1948), Too Late for Tears (1949), and Woman on the Run (1950). All of these were independently produced films that had fallen off the cultural and critical radar. Now we've turned our attention overseas, having preserved examples of classic Argentine noir such as Apenas un delincuente (1949), No abras nunca esa puerta (1952), Si muero antes de despertar (1952) and El vampiro negro (1953). These are all exceptional examples of noir that are virtually unknown to cinema culture outside Argentina—hell, they're barely known within Argentina. The Foundation now has donors from all over the world. We produce an exceptional quarterly e-magazine that explores noir is all its cultural and artistic permutations. We produce an array of festivals around the country. It's expanded in an extraordinary way.

MARK YOST: What was the first noir film you saw, and how did it hook you?

EDDIE MULLER: I'm not actually sure, but since I get asked this a lot I've settled on Thieves' Highway, a 1949 noir about the dangerous intrigues of the wholesale produce business, shot on location in San Francisco, my hometown. Seeing the city through a noir lens, and especially discovering aspects of the place that no longer existed, fueled both my imagination and my appreciation for historical context. Plus, the whole thing took place in the dead of night—I love stories about worlds that exist when the rest of the world is sleeping, and that describes a lot of noir. I got my initial dose of noir from watching Dialing for Dollars on afternoon TV, when I'd cut school and hide out to watch movies. All in all, that worked out pretty well for me.

Courtesy of the Film Noir Foundation

MARK YOST: Who do you think are the greatest male and female film noir stars and why?

EDDIE MULLER: Bogart is the essential male star. Whatever your personal preference may be, you have to accept Bogart as the pre-eminent icon of noir. His rise as an actor, moving from a second-string heavy to the leading man antihero, directly parallels the prevalence and popularity of film noir. Directors and cinematographers gave noir its look, but Bogart provided the attitude. His performance as Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon is seminal. It's the cultural touchstone for the wisecracking, cynical, and steadfastly existential philosophy that would become the underlying attraction of noir for so many people. There are other contenders—Robert Mitchum, Robert Ryan, John Garfield, Richard Widmark—but it was Bogart who lit the fuse.

It's tougher to cite a single actress. I'm tempted to say Barbara Stanwyck, but that might somehow diminish the fact that she's the greatest actress in the history of movies. Her range exceeded the boundaries of noir; she was great in everything. I also have great respect for Joan Crawford, who resurrected her career via film noir, starting with Mildred Pierce and going right through a series of exceptional dark melodramas of which she was the actual auteur. But there were so many wonderful actresses who did their most vivid work in this genre—Claire Trevor, Gloria Grahame, Ella Raines, Marie Windsor, Audrey Totter—it's impossible to single out one.

MARK YOST: Who do you think are the least-appreciated film noir male and female stars and why?

EDDIE MULLER: John Garfield doesn't get nearly the recognition he deserves. Not only was he the forerunner of actors like Brando, Clift and Dean, he also was the pied piper for a whole wave of New York theatre artists who, in his wake, made the transition from stage to screen. People are only now starting to appreciate his version of Hemingway's To Have and Have Not, retitled The Breaking Point (1950) as one of the greatest movies of the time—and Garfield essentially produced it himself for Warner Bros., which then stabbed him the back when the Communist witch-hunt heated up. It's still hard to believe he lived to be only 39.

As for the women, Ella Raines is overdue for reappraisal: she projected an progressive, almost proto-feminist image in her film noir roles—Phantom Lady, The Suspect, Uncle Harry, Brute Force, The Web, Impact. For an actress who didn't have a particularly long career, and rarely played deeply written or fleshed out characters, she managed to create a unique and surprisingly modern persona for herself.

Courtesy of the Film Noir Foundation

MARK YOST: Classic film noir is largely seen as the black and whites of the 1940s and '50s. What do you consider some of the great recent films—say in the past 20 years—that you think qualify as film noir?

EDDIE MULLER: Name a hot director of recent vintage and they probably have a film noir or two on their résumé. It's where a lot of filmmakers start out because they can assert some style and the stories aren't big-budget extravaganzas. If you can afford three actors, a hotel room and a gun you can make a film noir. Chris Nolan's Following, Paul Thomas Anderson's Hard Eight, Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs, the Coen Bros.' Blood Simple, Soderbergh's The Underneath, David Fincher's Seven … all early films in their careers that are extensions of classic film noir. This is just the American stuff. The best noir is now being done overseas, everywhere. Cannes this year was filled with noir.

MARK YOST: Tell us about NOIR CITY, the noir film festival you started in San Francisco, which now plays all over the country.

EDDIE MULLER: When I started the FNF, the mission was to simply preserve films. Now that mission has expanded three-fold: we're preserving the movie-going experience as it was in the old days—and most significantly we're trying to preserve the audience for these films, making sure that younger people have an appreciation for films from an earlier era, and that they can comprehend them in the proper context, not merely as camp. NOIR CITY festivals draw a devoted and passionate audience for these films. It's great fun and shows not sign of letting up. We're screening now in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Washington DC, Portland, Austin, Kansas City. We're considering additional venues if we can make it work logistically and economically. I also participate pretty regularly in festivals overseas. I just got back from a noir festival in Zagreb, Croatia!

NOIR CITY Magazine

MARK YOST: You're going to be hosting a film noir series on Turner Classic Movies this summer. Tell us what movies we'll see and why you chose them.

EDDIE MULLER: It's every Friday in June and July: TCM's "Summer of Darkness." It'll be 24 hours of noir every Friday, and I'll host four films each night during the prime time hours. TCM is basically utilizing its entire inventory of film noir, and I'm bringing in a few titles from the Film Noir Foundation collection. It's a terrific lineup, especially as it reaches all the way back to things like Fritz Lang's M (1931) and forward to titles like Night Moves (1974) and L.A. Confidential (1991). I didn't select all the films being shown, but I did pick the ones I wanted to present, for various reasons. It may have been because I felt the film was underrated, or there was an interesting connection between the films, or something was a personal favorite—or I simply had a great story I wanted to share. For me, there's some science to film programming, and a bit of art—but mostly it's fun.

MARK YOST: This fall you'll be hosting the Humphrey Bogart Film Festival in Key Largo, Florida. Tell us about that.

EDDIE MULLER: This year's Bogart festival is going to be as much about his beloved Lauren Bacall. I'll be co-hosting with Stephen Bogart, their son, whom I met earlier this year at another festival I hosted. I could readily see his parents in him. He's got his father's sarcastic humor. I'd interviewed his mother at length one time. "How'd that go?" Stephen asked me, dubiously. "She was delightful," I said. "You're sure that was my mother?" See, that was such a Bogart-Bacall thing to say. Anyway, I found her delightful because she was frank and interesting and generous with her time. There were other folks there that day that certainly did not share my opinion. Bacall did not suffer fools. I doubt I will either when I'm in my eighties.

MARK YOST: Tell us about the films that will be shown at the festival, and which ones you think are the best, either in terms of Bogart's performance, or their place in the film noir pantheon.

EDDIE MULLER: It's packed with noir, I can tell you that. They're showing all four Bogart & Bacall films, To Have and Have Not, The Big Sleep, Dark Passage and Key Largo. Plus The Maltese Falcon, Casablanca, Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Sabrina, The African Queen, The Caine Mutiny. That's a lot of great films before you even get to my personal favorite, In a Lonely Place. It's my favorite film of all time, not just my favorite Bogart picture, so I'm looking forward to introducing that one, especially to people who may not have seen it. I've not been to the festival before, so I'm thrilled they invited me to co-host. It looks like a lot of fun, as especially befitting of Bogart there is plenty of cocktail time built into the schedule. In his honor, maybe I'll declare that I won't work past 4 p.m. because it cuts into my drinking time.

MARK YOST: You're also a respected author and filmmaker in your own life. Tell us about that aspect of your life.

EDDIE MULLER: Funny isn't it—that's like an afterthought now. Once it was the direction my life was taking. Then this whole Czar of Noir business happened. But I self-identify as a writer, always have. The way I see it, I tell stories. That's essentially what I do with my life: tell stories. Sometimes they take the form of short stories, or novels, or plays, or films, or simply standing in front of an audience or camera and talking. As long as I don't start confusing the fiction with the non-fiction, I'll be okay. I'll be the guy in the old folks' home who never shuts up.

MARK YOST: What's next for Eddie Muller?

EDDIE MULLER: More stories, obviously. I'm editing a noir anthology for Akashic Books right now, and working on a third novel in my Billy Nichols crime fiction series. There's a screenplay I'm developing (a couple, actually) and we'll be ramping up the restoration work at the Film Noir Foundation. And, of course, whatever Turner Classic Movies has on tap for me. I'm game. That's a terrific gig and I really enjoy being a torchbearer for classic cinema, especially when it comes to presenting it to a younger, contemporary audience.

Links:

Film Noir Foundation

NOIR CITY Film Festivals

Eddie Muller

Mark Yost at Stay Thirsty Publishing

Mark Yost